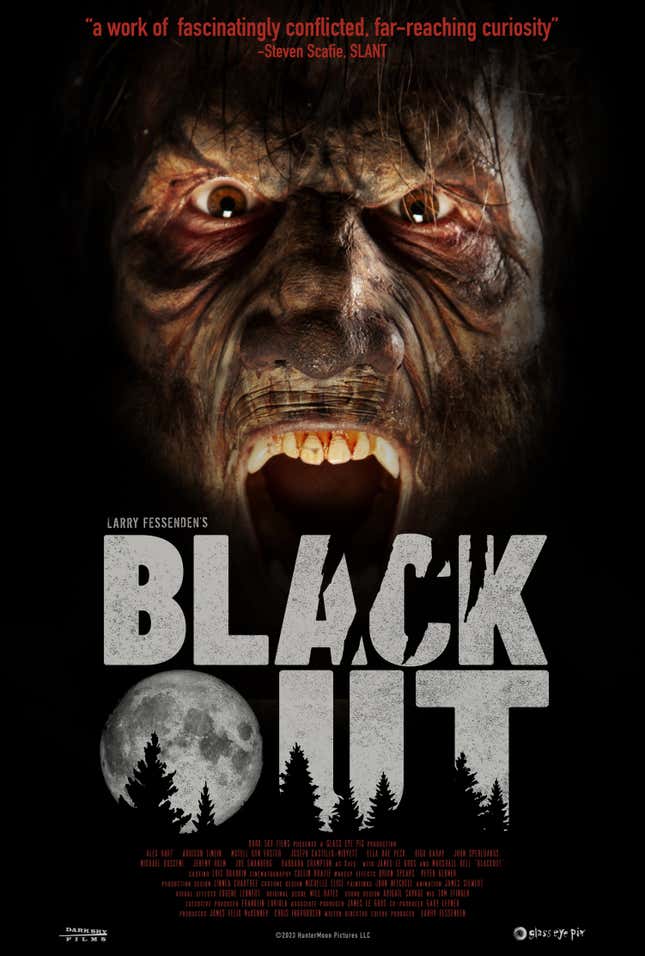

If you’re a fan of indie horror, chances are you’re well familiar with the work of Larry Fessenden—both as a director (Habit, The Last Winter, Beneath) and an actor (Session 9, You’re Next, Jakob’s Wife, The Dead Don’t Die). His latest movie, werewolf tale Blackout, arrives today, and io9 got a chance to ask him all about his new release, as well as his career to date.

What follows is an edited and condensed version of our interview.

Cheryl Eddy, io9: The most recent season of True Detective, Night Country, immediately made me think of your 2006 movie The Last Winter. Did you happen to watch it?

Larry Fessenden: I watched the show, which I enjoyed quite well. I love snowy movies. Jodie [Foster] was awesome. And actually, I liked her costar [Kali Reis] even more. So, I liked a lot of it. And, yes, I was absolutely struck by The Last Winter vibe. And some people, like a couple friends, wrote me [about the similarities], and then there was even some of those lists that they make on the internet saying, “if you like True Detective, you should watch these weird movies no one’s ever heard of.” I’m not accusing anybody of ripping me off, but it’s fun to see that vibe. I really enjoyed that part of it.

io9: Until Dawn, the hugely popular interactive horror game that you co-wrote, is being made into a feature film by David F. Sandberg and Gary Dauberman. Are you involved at all? What are your hopes for the big-screen adaptation?

Fessenden: Well, it’s a puzzle because of course, the beauty of Until Dawn is it was designed to be like a movie, but the fact that you have branching choice points makes it meta in a different way. So I will actually be curious to see how traditional they are with the story. I mean, you could just tell a version of the story and that will be it. And hopefully the characters are well-drawn and people will enjoy it. But, actually, Graham and I—Graham Reznick was my co-writer—we did pitch it five or seven years ago all the way up in the ranks at Sony, I think. And I think our idea was maybe too whackadoodle for them; we were trying to lean into the fact that this is a video game already, and I can’t remember—Graham’s smarter than me, he can remember—but it was too eccentric for them. I think I should be asked to play the character that I played in the game because it’s just a walk on. It won’t matter. They can’t probably get a movie star, so why not get me?

io9: Speaking of that—you’re almost as well-known for your acting roles as you are for directing, and you have equally lengthy careers in both fields. Do you have a preference between the two? When you’re taking an acting role these days, what attracts you to a project or a character?

Fessenden: Well, I don’t have an agent or anything. I sometimes audition, but mostly, it just comes my way. I always read [about] real movie stars talking about movies they’ve turned down—which is funny because, I mean, I don’t have much to turn down, so I just do what comes my way. It’s a paycheck. It’s a great way to be on another person’s set. Often I know the director or I want to support someone. A lot of these are cameos, but I get bigger parts sometimes, and that’s really great. I acted with Barbara Crampton in a movie by Travis Stevens [Jakob’s Wife], and that was fun. And, notoriously, I’m in the Scorsese movie [Killers of the Flower Moon], which of course is beyond fun. That’s literally a seminal life experience to be on his set. So, it’s a great way to be involved in a movie. I couldn’t commit to [acting] as a career, but I do quite a bit of it. I was an actor when I was young, and that’s what I thought I wanted to do. But then I got attacked by the bug of filmmaking, and I wanted to do everything else on the set, too.

io9: You founded your production company in the 1980s. What’s it been like sort of surfing the wave of indie filmmaking in the decades since? What are the biggest challenges facing an independent filmmaker in 2024 that are unique to these specific times?

Fessenden: It’s obviously financing and distribution—even if you managed to get the money from a dentist to to make a small film, and you make it, you’re just one among many because of the digital revolution. A lot of people can get a movie off the ground, and god love ‘em, for 100 grand or less or a little bit more—the budget levels have come down and that’s tough. Even the films I was producing 20 years ago, there was a little bit more money, just for the salaries. The whole thing that I was trying to do is make it sustainable to be a gaffer or a grip, but the sad thing is that I keep my budget so low that I’m really sort of preying on their goodwill. That’s why I use youngsters; I work with young people because they’re still learning their craft and they’re hungry and they’re idealistic. That’s sort of the sweet spot of when you want to meet someone who’s trying to be an artist or in the arts in some way.

So, yeah, [to keep answering your question]: distribution [today] is really tough. They don’t pay for your movie anymore. You don’t get a minimum guarantee. And streaming doesn’t really report the numbers in an accurate or fair way. [It’s] like you’re just volunteering, it’s as if you made shoes and you just made the shoe and gave them away. The whole thing is really perverse. And it is because of streaming. It’s the way the industry is built now and there’s no respect for little films. The idea is that you’re doing it out of love in order to make bigger films. Well, what if you just like the aesthetic of the little film? So it’s tough, actually… like the TV rights, the theatrical, you’d have a run, then you had the Blu-ray or DVD rights, and then you had obviously foreign [rights], but there were more avenues with which to build your payback and get your investors their money, so they’d do it again. All of that is just, it’s literally vanished. It’s very difficult.

io9: Your latest film, Blackout, feels like an indie drama… but it also happens to be a werewolf tale. What made you want to frame a classic creature-feature story in that way?

Fessenden: That’s literally just been my entire approach to this genre, which I love. I grew up on old-fashioned horror movies with werewolves and so on, but I took them very seriously. I cared about the characters. The character Larry Talbot, played by Lon Chaney Jr, is a very poignant and lonely, pathetic character really, with this curse. But then as I got older, I could see that [old-fashioned horror movies] were sort of rickety. And I was engaged with Scorsese and Robert Altman and the movies of the ‘70s. I wanted to bring that immediacy and naturalism element into the genre space. I appreciate the way you describe my movie, because that is what I’m doing: I’m literally making indie films that have monsters in them. I think that for me, that’s how I experience life. There is sort of always a monster in my life, which is death lurking over me. I’m paranoid—I see the world as this intolerably difficult place. In a way, there is an element of horror just in the way I perceive the world, as well as yearning for beauty and so on. So those are things that an indie film does; they have the nuance and the subtlety and the celebration of the daily moments for details. And when you have a monster, that makes it more fun.

io9: Blackout also brings in those environmental themes that were in The Last Winter. What do you think fascinates you about that intersection between horror and the environment?

Fessenden: Well, what is more horrifying than what we’re doing to the planet?My movies are also about addiction and alcoholism and self-betrayal. And I think the environment and what we continue to do to our living space, as well as each other, is just appalling. It is the stuff of horror. It’s a self-betrayal. It’s self-destructive. We’re committing suicide on the installment plan, which is a line from one of my movies. It was a guy saying that’s why he smokes, but that’s what humanity is doing. I just take it very personally.

io9: The main character in Blackout is pretty recently a werewolf, but his life was already rock-bottom even before his transformation. What made you want to focus on a protagonist in that state?

Fessenden: What I do is I have the attack be the thing that’s haunting him. He’s an artist, so he’s kind of an outsider. His community seems to have a problem with his father. His father never understood his art, so he just feels alienated. And then he’s clearly a drinker, and he’s lost his girlfriend. It’s not just like this guy turned into a werewolf; it’s like, who invites the darkness into their lives? Somebody who’s struggling already … The way we did the makeup, you can see the actor underneath. You’re not being fooled into, “this is some grandiose mythological creature.” It’s really just a dude, with some real serious psychological problems. Obviously you’re enjoying, hopefully, that he’s clearly a werewolf or some version of the Wolf Man, but it’s trying to play with the werewolves in our lives, the curses, the burdens.

[To me, when he’s bitten by a werewolf], that is a moment that he crosses over into the dark side. It’s sort of, he allows this darkness into his life. He’s painting, then he hears a noise and he steps outside. He literally steps over the threshold. And, in my mind, I really always want to operate on a metaphorical level as well as a literal one, because I’m sort of saying that life is imbued with meaning, but it’s actually completely brutish, short, and without meaning. But we infuse the meaning. So I want to capture moments where the mythology creeps into our daily life. It’s just like this tension between a yearning for for definition and mythology, and yet this sort of the everyday life, the blandness of where you’re responsible for your own undoing.

io9: Is there a dream project that you are hoping to make that you have yet to tackle in your long career?

Fessenden: I want to make one more of these monster movies. Maybe with all of them in it. I don’t know how I’ll be able to pull it off—financing and so on. So we’ll see. But that beyond that, in a way, I just want to get that idea out. And then, I don’t know—[note: he says this jokingly] maybe I’ll make a musical or a Christmas movie. I don’t know what the next thing would be. And I don’t know if the world cares. So I just will see what comes to me and what’s possible. It is unfortunately, a lot about budget and all those things. I love making movies. But it’s also exhausting.

Blackout opens in theaters and on digital/VOD platforms today, April 12.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.

Trending Products

Cooler Master MasterBox Q300L Micro-ATX Tower with Magnetic Design Dust Filter, Transparent Acrylic Side Panel…

ASUS TUF Gaming GT301 ZAKU II Edition ATX mid-Tower Compact case with Tempered Glass Side Panel, Honeycomb Front Panel…

ASUS TUF Gaming GT501 Mid-Tower Computer Case for up to EATX Motherboards with USB 3.0 Front Panel Cases GT501/GRY/WITH…

be quiet! Pure Base 500DX Black, Mid Tower ATX case, ARGB, 3 pre-installed Pure Wings 2, BGW37, tempered glass window

ASUS ROG Strix Helios GX601 White Edition RGB Mid-Tower Computer Case for ATX/EATX Motherboards with tempered glass…